Georg Maria Guntesperger

La creatività spesso necessita differenti forme espressive per manifestarsi e dare sfogo alla sua poliedricità: Georg Maria Güntensperger, architetto svizzero di grande talento e con approccio fortemente creativo e visionario negli interni ed esterni da lui realizzati, sente che la sua indole creativa non riesce a trattenersi e a fermarsi su un solo canale, ha bisogno di esprimersi su più livelli e a spaziare nei vari settori artistici, perché anche nei suoi lavori architettonici esattamente di arte si tratta. Avvicinabile alla corrente contemporanea che è seguita al Modernismo Architettonico, di cui furono massimi rappresentanti Antoni Gaudì e Le Courbusier, ha dato vita a strutture fiabesche progettando e realizzando gli interni della villa dello scrittore C.F. Fray in arte Akron, dallo stesso proprietario definito il suo castello magico, in cui la mansarda in legno con soffitto merlettato dialoga con il resto degli interni magistralmente adattati all’ambiente e, inevitabilmente, anche con gli esterni, a loro volta suggestivi e in linea con lo stile fiabesco della palazzina e perfettamente armonizzati con la natura circostante. La boutique Aladin di San Gallo è un altro chiaro esempio di quanto questo architetto svizzero sia orientato alla bellezza ma anche all’eccentricità delle linee e delle forme che diventano protagoniste tanto quanto i mobili scelti e gli elementi d’arredo; e ancora, in una sauna realizzata qualche anno fa, è evidente l’alternanza tra vuoti e pieni in sinergia con la pavimentazione che sembra essere una continuazione delle panche e degli infissi che la racchiudono, naturali ed essenziali tanto quanto elegante e raffinato è il marmo a motivi dinamici scelto per la pavimentazione.

Sauna

Legno, pietra e marmo sono i materiali con i quali misura la sua creatività, la sua capacità di coniugare uno sguardo da sognatore in grado di creare atmosfere morbide e incantevoli ma al tempo stesso pratiche e funzionali.

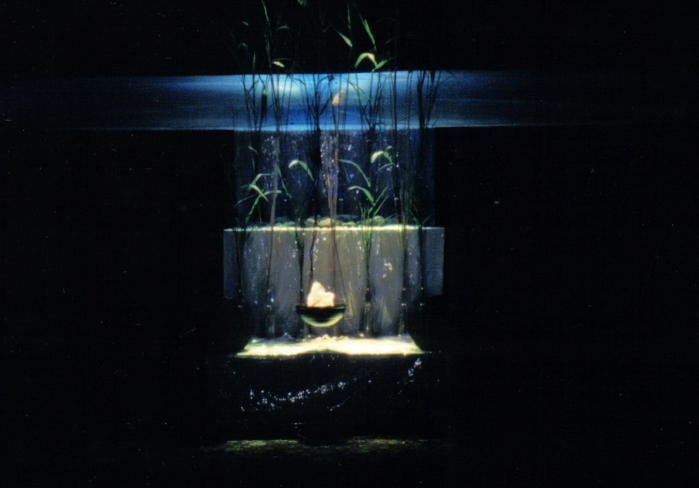

Altro suo canale espressivo è la realizzazione di scenografie di luci per spettacoli teatrali, in cui i pannelli e gli oggetti creati per essere visti e ammirati sul palcoscenico diventano oggetto e soggetto del rifrangersi delle sue luci, punto focale su cui dirigere l’attenzione dello spettatore e condurlo per mano verso l’importanza di quei dettagli funzionali alla rappresentazione trattata.

Scenografie di luci

Gli elementi scenici vengono amplificati e sottolineati in virtù dei raggi luminosi sapientemente combinati da Güntensperger. Negli ultimi tempi la sua indole creativa si è spostata verso una sinergia tra musica e poesia, un’interpretazione su note musicali di liriche di grandi maestri internazionali o elvetici in cui ciò che conta è l’accordo tra melodia e metrica, tanto quanto nelle sue architetture lo è tra gli interni e gli esterni, i vuoti e i pieni, le linee e le geometrie delle sue creazioni architettoniche. Associa poesie abbinandovi musiche di grandi compositori, come se fossero un elemento scenico mobile nel quale il suono accompagna e si avvolge alle parole in un dipanarsi interpretativo reciproco, dove le frasi sembrano essere portate dalle note musicali come su un tappeto volante che le accompagna nel ritmo e nella modalità espressiva. Sceglie dunque letteralmente di costruire una canzone tramite la poesia; un esempio è il De profundis clamavi di Charles Baudelaire, tratta dalla celebre raccolta di poesie Les fleurs du Mal che ha combinato con il brano Gradus ad Parnassum per pianoforte di Claude Debussy, dal suo album Children’s Corner. Oggi abbiamo l’opportunità di conoscere più approfonditamente questo architetto, scenografo di lui, e creativo a tutto tondo, attraverso la sua voce.

Georg, lei ha uno stile architettonico decisamente al di fuori degli schemi tradizionali, il suo approccio eccentrico e singolare può essere avvicinato, nell’intenzione di andare oltre, a quello di Frank Gery, Zaha Adid, Frank Lloyd Wright; quali tra questi grandi maestri dell’architettura contemporanea l’ha ispirata di più? A chi di loro si sente più vicino per affinità creativa?

Frank Lloyd Wright è stato uno dei pionieri del Modernismo Classico e di uno stile che plasma la strada fino ad oggi, in particolare i suoi tentativi di superare la perpendicolarità, che ancora oggi governa il settore edile per puro pragmatismo, erano visionari e trovarono un terreno fertile tra i suoi contemporanei più giovani come per esempio le Corbusier. Per me personalmente, tuttavia, Antoni Gaudi è stato ancora più importante, lui ha superato l’ortogonalità non solo per ragioni estetiche ma per rivoluzionare da zero l’ingegneria strutturale degli edifici e nel suo approccio vedo quello di chi rivoluziona anche radicalmente la tecnologia edilizia come i cosiddetti decostruttivisti Daniel Libeskind, Wolfgang Prix e soprattutto la meravigliosa Zaha Hadid. Mentre Frank Gehry, certamente anche lui decostruttivista, mi stupisce davvero molto per la radicalità delle sue strutture architettoniche. In realtà lui è uno scultore e i suoi modelli, fatti a mano, sono i veri prodotti della sua arte, che sono determinanti delle forme dell’edificio e diventano scannerizzati, analizzati e visualizzati elettronicamente mentre il resto è progettazione assistita da computer, un’arte da non sottovalutare; Frank Gehry stesso fu sorpreso dalla precisione dei programmi dei suoi informatici catalani nell’ambito della realizzazione del museo Guggenheim a Bilbao. In sintesi posso affermare di vedermi come un epigone di quei geni dell’architettura e tutti sono stati importanti per me. “Il nostro è il destino degli epigoni, che vivono nell’ampio regno intermedio”. Cit. Gottfried Keller.

Qual è stato il suo lavoro più complesso e soddisfacente in cui ha potuto dare libero sfogo alla sua meravigliosa visionarietà senza avere alcun limite creativo?

Non succede mai che non ci siano confini alla creatività e sicuramente quello più frenante è la capacità limitata della propria mente, ma ve ne sono anche molti altri: quelli tecnici, legali, economici, estetici così come già la formula base dell’architettura in cui la forma segue la funzione, pone dei limiti. L’architettura non è quasi mai fine a se stessa. Tuttavia io sono stato quasi sempre fortunato poiché i miei clienti mi hanno quasi sempre dato la massima libertà possibile entro i parametri indicati e nel caso particolare della Casa Balestra a Gerra Gambarogno, in cui io ero sia committente che appaltatore dunque il risultato è il più coerente.

Nel teatro lei lavora con le luci, che in fondo costituiscono una sorta di architettura del palcoscenico, un tassello fondamentale per la riuscita dello spettacolo e per dare più struttura allo scenario. Ci racconta di quest’altra sua espressione creativa? Quanto l’architettura alimenta il suo ruolo di scenografo di luci e quanto il secondo influenza il primo?

Un approccio architettonico alla progettazione di un palcoscenico è centrale, ma deviando dal carattere statico dell’architettura, una scenografia è soggetta a un processo dinamico e drammatico, paragonabile alla differenza tra una foto e un film, quindi, è qualcosa di molto diverso e richiede inoltre abilità sceniche teatrali e musicali.Per esempio, le agili luci di marcia scandiscono e accompagnano le melodie della musica sul palco e i vari cambiamenti degli accordi di colore, sofisticate combinazioni di differenti filtri colorati davanti ai proiettori, corrispondono nel loro effetto alla strumentazione e teatralizzazione della musica a cui devono accordarsi.Il compositore russo Alexandr Skrjabin del Prométhée ou le Poème du Feu, sognava un organo di luce o almeno un pianoforte di luce, un strumento che al giorno d’oggi è stato realizzato e lui ne sarebbe entusiasta.

Scenografie di luci

Ha iniziato da poco a seguire un nuovo percorso espressivo, quello di armonizzare testi poetici a musiche classiche che siano affini all’intensità lirica dei versi. Può spiegare più nel dettaglio ai lettori in cosa consiste questo suo nuovo percorso e cos’è che l’ha spinta a misurarsi con questa sfida?

La musica ha sempre giocato un ruolo importante nella mia vita, c’era molta musica a casa dei genitori e per poter realizzare un ensemble da camera familiare gli strumenti erano stati scelti selettivamente per noi bambini; a me è stato assegnato il violoncello e in seguito ho frequentato lezioni per ben quattordici anni seguite dagli studi di pianoforte così durante e dopo i miei studi di musicologia, fisica e matematica all’Università di Zurigo ho cominciato a comporre. Inizialmente per diverse formazioni, per lo più quartetti strumentali, a volte in stile dodecafonico o seriale, ma poi aggiunsi anche opere per pianoforte sfruttando in questo modo la possibilità di accompagnare le note con la mia voce cantando le mie canzoni e arie d’opera generando un processo autodidattico. Di conseguenza ho fondato le basi per diventare un cantautore che scrive i testi e li mette in musica anche ed è in questo modo che sono nate varie canzoni dialettali come Of dä Chamhald

https://static.wixstatic.com/mp3/b5b6c1_409f71eaed0343c18b3a66dcc70af543.mp3

Quali sono i suoi prossimi progetti? Sarà più orientato a portare avanti un canale espressivo piuttosto che un altro oppure li porterà avanti in contemporanea?

Come artista mi sento quasi come se fossi un pentatleta che deve mettersi alla prova in varie discipline molto differenti tra loro e che in nessuna è in grado di fornire prestazioni d’eccellenza massimale, ma grazie alla combinazione di tutte, ottiene comunque risultati sportivi. Nel mio futuro ho intenzione di continuare a coltivare la mia poliedricità e a dedicarmi a varie forme d’arte, perché è ciò che amo fare e che soddisfa la mia natura di sperimentatore.

GEORG MARIA GÜNTENSPERGER-CONTATTI

Email: georgmaria@bluewin.ch

Marta Lock’s interviews:

Georg Maria Güntensperger, visionary architecture and music

Creativity often needs different forms of expression to express itself and give vent to its versatility: Georg Maria Güntensperger, a highly talented Swiss architect with a strongly creative and visionary approach to the interiors and exteriors he has created, feels that his creative nature cannot be restrained and stop at just one channel, it needs to express itself on multiple levels and to range over the various artistic sectors, because his architectural works are exactly that: art. Close to the contemporary trend that followed Architectural Modernism, of which Antoni Gaudì and Le Courbusier were the greatest representatives, he has created fairy-tale structures by designing and building the interiors of the villa of writer C.F. Fray, alias Akron, which the owner himself called his magic castle, in which the wooden mansard with its lacework ceiling dialogues with the rest of the interior, masterfully adapted to the environment and, inevitably also with the exterior, which in turn is evocative and in line with the fairytale style of the building and perfectly harmonised with the surrounding nature. The Aladin boutique in St. Gallo is another clear example of how this Swiss architect is oriented towards beauty but also towards the eccentricity of lines and forms, which become the protagonists as much as the chosen furniture and furnishings; and again, in a sauna built a few years ago, the alternation of full and empty spaces is evident, in synergy with the flooring which seems to be a continuation of the benches and frames which enclose it, as natural and essential as the marble with dynamic patterns chosen for the flooring is elegant and refined. Wood, stone and marble are the materials with which he measures his creativity, his ability to combine a dreamer’s eye capable of creating soft and enchanting atmospheres that are at the same time practical and functional. Another of his expressive channel is the production of light scenographies for theatrical performances, in which the panels and objects created to be seen and admired on the stage become the object and subject of the refraction of his lights, the focal point on which to direct the spectator’s attention and lead him by the hand towards the importance of those details that are functional to the representation treated. The scenic elements are amplified and emphasised by virtue of Güntensperger’s skilfully combined rays of light. Lately, his creative nature has shifted towards a synergy between music and poetry, an interpretation on musical notes of lyrics by great international or Swiss masters in which what counts is the harmony between melody and metrics, just as in his architecture it is between interior and exterior, empty and full spaces, lines and geometries of his architectural creations. He associates poems with music by great composers, as if they were a mobile scenic element in which the sound accompanies and wraps around the words in a reciprocal interpretative unravelling, where the sentences seem to be carried by the musical notes as if on a flying carpet that accompanies them in rhythm and expressive mode. He therefore literally chooses to construct a song through poetry; an example is Charles Baudelaire’s De profundis clamavi from the famous collection of poems Les fleurs du Mal, which Güntesperger combined with Claude Debussy’s Gradus ad Parnassum for piano, from his album Children’s Corner. Today, we have the opportunity to get to know this architect, set designer and all-round creative artist in greater depth through his voice.

Georg, you have an architectural style that is decidedly outside the traditional schemes, your eccentric and singular approach can be compared, in its intention to go beyond, to that of Frank Gery, Zaha Adid, Frank Lloyd Wright; which of these great masters of contemporary architecture has inspired you the most? Which of them do you feel closest to in terms of creative affinity?

Frank Lloyd Wright was one of the pioneers of Classical Modernism and of a style that shapes the way to this day, in particular his attempts to overcome perpendicularity, which still governs the building industry today out of pure pragmatism, were visionary and found fertile ground among his younger contemporaries such as Le Corbusier. For me personally, however, Antoni Gaudi was even more important, he went beyond orthogonality not only for aesthetic reasons but to revolutionise the structural engineering of buildings from scratch and in his approach I see that of those who also radically revolutionise building technology such as the so-called deconstructivists Daniel Libeskind, Wolfgang Prix and above all the wonderful Zaha Hadid. Whereas Frank Gehry, who is certainly also a deconstructivist, really amazes me with the radicalness of his architectural structures. In reality he is a sculptor and his models, made by hand, are the real products of his art, which are determinants of the forms of the building and become scanned, analysed and visualised electronically while the rest is computer-aided design, an art not to be underestimated; Frank Gehry himself was surprised by the precision of the programmes of his Catalan computer scientists when he built the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao. In short, I can say that I see myself as an epigone of those architectural geniuses, and they have all been important to me. “Ours is the destiny of epigones, living in the vast intermediate realm”. Cit. Gottfried Keller.

What has been your most complex and satisfying work in which you have been able to give free rein to your wonderful visionary nature without having any creative limits?

It never happens that there are no limits to creativity and certainly the most limiting one is the limited capacity of one’s own mind, but there are also many others: technical, legal, economic, aesthetic ones as well as the basic formula of architecture, in which form follows function, sets limits. Architecture is almost never an end in itself. However, I have been lucky because my clients have almost always given me the greatest possible freedom within the parameters indicated, and in the particular case of Casa Balestra in Gerra Gambarogno, where I was both client and contractor, so the result is the most consistent.

In the theatre you work with lights, which basically constitute a sort of architecture of the stage, a fundamental element for the success of the show and to give more structure to the scenario. Can you tell us about this other creative expression of yours? How much does architecture feed your role as a lighting designer and how much does the latter influence the former?

An architectural approach to stage design is central, but deviating from the static character of architecture, a set design is subject to a dynamic and dramatic process, comparable to the difference between a photo and a film, therefore, it is something very different and also requires theatrical and musical stage skills. For example, the agile marching lights punctuate and accompany the melodies of the music on stage, and the various changes of colour chords, sophisticated combinations of different coloured filters in front of the projectors, correspond in their effect to the instrumentation and theatricalisation of the music they have to match. The Russian composer Alexandr Skrjabin’s Prométhée ou le Poème du Feu, dreamed of an organ of light or at least a piano of light, an instrument that has now been realised and he would be thrilled.

You have recently started to follow a new expressive path, that of harmonising poetic texts with classical music that is akin to the lyrical intensity of the verses. Can you explain in more detail to our readers what this new path consists of and what prompted you to take on this challenge?

Music has always played an important role in my life, there was a lot of music in my parents’ house and in order to create a family chamber ensemble, the instruments were selectively chosen for us children; I was assigned the cello and then attended lessons for fourteen years followed by piano studies, so during and after my musicology, physics and mathematics studies at the University of Zurich, I began to compose. Initially for different formations, mostly instrumental quartets, sometimes in a twelve-tone or serial style, but later I also added works for piano, thus using the possibility of accompanying the notes with my voice by singing my own songs and opera arias in a self-taught process. As a result, I founded the basis for becoming a songwriter who writes lyrics and sets them to music as well, and it is in this way that various dialect songs were born, such as Of dä Chamhald in the Appenzell idiom. The song De profundis clamavi, on the other hand, is a special and isolated case because it was already written in poetic language that I transformed into prose: to a piano piece by Claude Debussy, an arrangement of a piece from Munzio Clementi’s Gradus ad Parnassum, I added Charles Baudelaire’s poem De profundis clamavi, which in turn refers to the biblical psalm De profundis clamavi ad te, Domine.

What are your next projects? Will you be more inclined to pursue one channel of expression rather than another, or will you pursue them simultaneously?

As an artist, I feel almost as if I were a pentathlete who has to test himself in various very different disciplines and who in none of them is able to deliver a maximum performance of excellence, but thanks to the combination of all of them, still achieves sporting results. In my future, I intend to continue to cultivate my versatility and devote myself to various art forms, because that is what I love to do and it satisfies my nature as an experimenter.