di Marta Lock

Tedesco, nato a Colonia ma contraddistinto da una personalità eclettica e dinamica che si affianca a un atteggiamento più logico e razionale proprio perché il suo essere artista lo fa entrare nella dimensione della creatività, quella in cui tutto è possibile, in cui il colore diviene guida ma dove la sperimentazione e il desiderio di andare oltre e superare le conoscenze già acquisite costituisce un atteggiamento funzionale all’elaborazione dell’opera d’arte. Asseconda la sua inclinazione artistica fin da ragazzo Hans Adam, iscrivendosi alla facoltà di Pittura libera presso l’Università degli Studi di Colonia, a cui segue un’esperienza professionale come progettista multimediale; il suo amore per la cultura non si limita all’espressione plastica bensì sente il bisogno di misurarsi anche con altre discipline, come quella della scrittura in virtù della quale diviene membro del Circolo letterario di Saarbrücken. Il suo cammino creativo dunque è molteplice e inarginabile, e si manifesta in particolar modo nella sua attitudine alla sperimentazione in cui coniugare le forme geometriche all’interazione tra colori che appaiono come tasselli da mettere in dialogo l’uno con l’altro evidenziando la capacità di osservazione di Hans Adam, il suo voler armonizzare l’impulso creativo con un’attitudine analitica che quasi inconsapevolmente si traduce in racconto metaforico della realtà contemporanea. Sì perché le sue sculture non solo sembrano cercare il loro posto, la loro dimensione, all’interno dello spazio circostante come se l’alternanza di vuoti e pieni che le caratterizza rappresentasse l’avvicendarsi nella realtà quotidiana di quegli alti e bassi con cui ciascun individuo inevitabilmente si trova a misurarsi, ma la contrapposizione cromatica identifica e sottolinea a livello visivo il contrasto o la contiguità con cui l’artista descrive le luci e le ombre, mette in evidenza i volumi e racconta la solidità opposta all’inconsistenza che contraddistinguono la realtà oggettiva. L’opera Vier Kreise Modell (Modello a quattro cerchi)

racconta perfettamente il doppio approccio di Hans Adam, quell’equilibrio tra leggerezza e imponenza in cui il colore laccato diviene elemento compositivo tanto quanto lo sono il compensato e il legno usati per la grande struttura pensata per essere attraversata dall’uomo, dunque introducendo l’elemento spazio che non è solo qualcosa da ricercarsi all’esterno bensì anche all’interno della scultura che diviene pertanto accogliente simbolo di inclusione. In Ohne Titel 3 (Senza titolo 3)

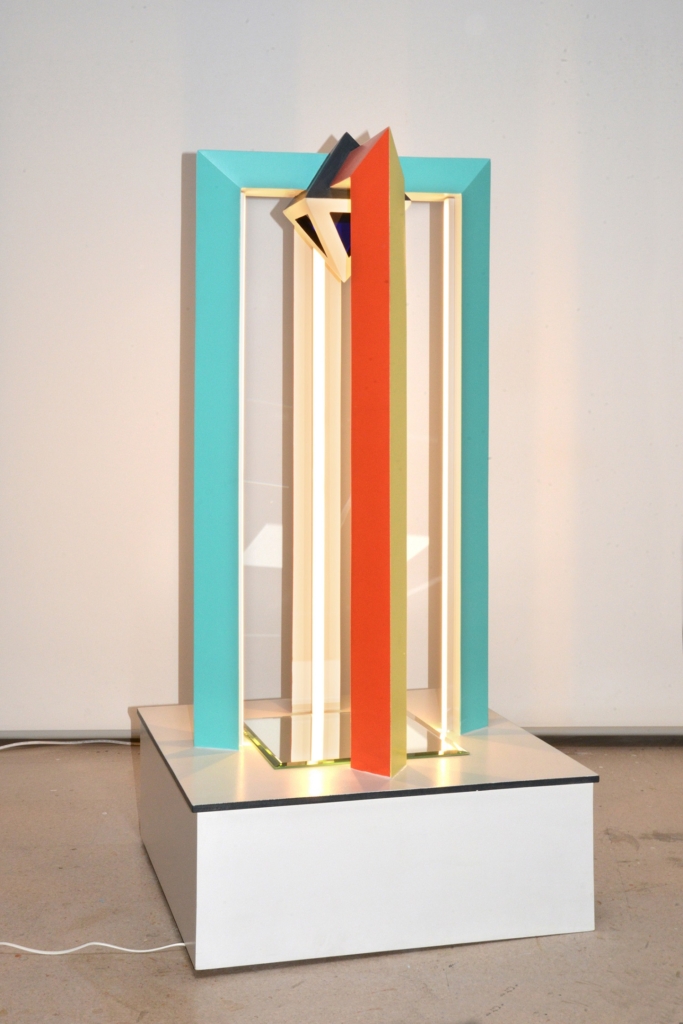

invece, l’artista sceglie di allargare la sperimentazione compositiva e il dialogo tra diversi elementi che in virtù del suo tocco creativo entrano in perfetta armonia; dunque legno, plexiglas, specchio, multiplex, led, e colore laccato costituiscono una scultura in cui lo spazio, ancora una volta, entra all’interno per alleggerirne i volumi ma al tempo stesso infonde nell’osservatore un senso di concretezza, di elegante saldezza donato dall’alternanza tra luce e colore attraverso cui Hans Adam sembra suggerire di andare oltre l’apparenza, di entrare nella superficie, costituita dai volumi più esterni, per poi scoprire quanto altro si nasconde dietro di essi. Nell’approccio creativo dell’artista dunque ciò che conta è la base geometrica che diviene mezzo di ricerca, di studio approfondito di materia e di cromaticità, del loro dialogo e del rapporto con l’esterno, e solo in un secondo momento, contrariamente all’intenzione e al concetto di Adam che l’arte non debba avere una connessione con il mondo interiore, quella sperimentazione diviene metafora del mondo che lo circonda, permettendogli di far emergere contraddizioni e aspetti del vivere contemporaneo solo apparentemente asettico e privo di emozionalità ma in realtà molto più consistente di quanto creda di dover dimostrare di essere. Andiamo ora a conoscere meglio questo dinamico scultore attraverso le domande dell’intervista.

Hans, lei fin da giovane ha seguito il suo impulso creativo che le ha permesso di sperimentare in percorso artistico a seguito del quale ha scelto di aderire all’Astrattismo Geometrico. Come mai questa scelta? È stato un punto di arrivo ragionato oppure è arrivato spontaneamente seguendo il suo istinto creativo? Le motivazioni che mi hanno condotto allo stile attuale sono molteplici. Quando andavo a scuola, la pittura era come una sorta di linguaggio per me, e da bambino, all’età di sei o sette anni, sapevo già di voler diventare pittore. Nonostante la resistenza che trovavo nel mio ambiente familiare, sono riuscito a studiare pittura dopo la mia formazione professionale come giardiniere. Anche durante gli studi ho esposto in strada le copie che eseguivo delle opere dei grandi maestri come Rembrandt, Van Dyck e Rubens e questo mi ha permesso di finanziare parte dei miei studi, di acquistare i colori e altri utensili per dipingere. Qualche anno più tardi, alla ricerca di nuove strade, sono arrivato a un punto in cui ho messo in discussione la mia pittura. Quello è stato il punto di svolta della mia vita. Sentivo il bisogno di vedere il mondo, sono stato in India e a Bali dove ho lavorato soprattutto nell’artigianato. Con tutte le nuove esperienze e le impressioni travolgenti provenienti da mondi stranieri ho scoperto nuove possibilità di esprimere la mia creatività. Forme geometriche, superfici, corpi, spazi, le loro interazioni, questo era ciò che mi affascinava. Mi sono sentito giocosamente trasportato indietro al periodo della mia infanzia ed ero stimolato dal poter creare io con l’arte quelle forme che da piccolo mi attraevano, le diverse sfaccettature della geometria erano e sono ancora oggi irresistibili. La sperimentazione e la percezione fisica degli elementi e gli spazi, così come l’atto creativo coinvolto, mi danno grande grande appagamento e profonda soddisfazione.

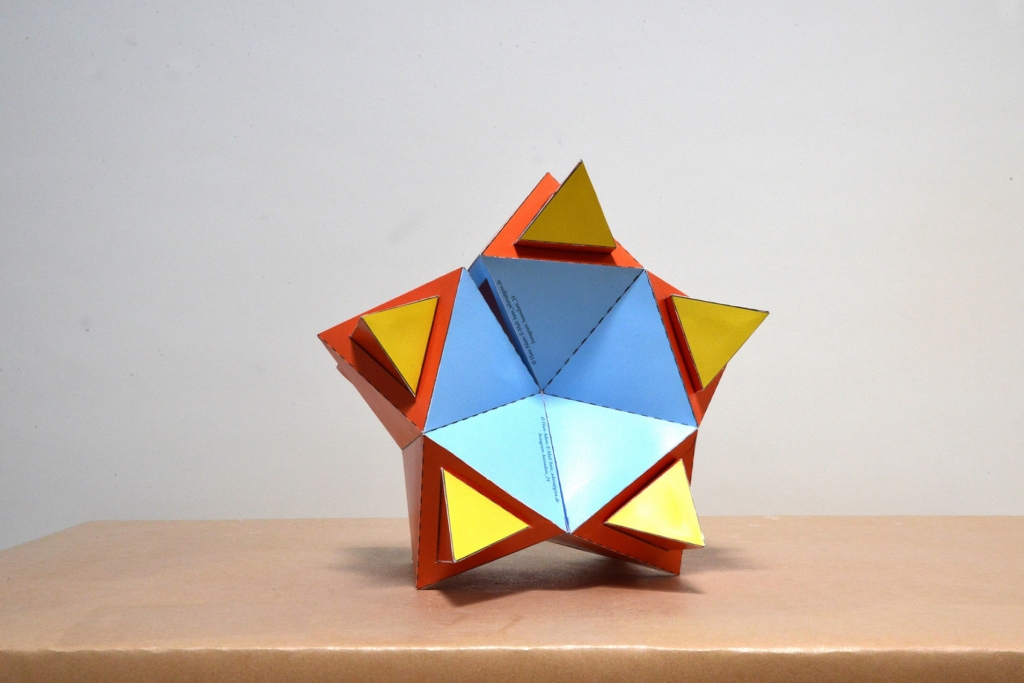

Fuenf Oktaeder Modell (Modello a cinque ottaedri)

Lei ha una personalità molto dinamica ed eclettica, come concilia questo suo aspetto caratteriale con l’approccio logico e razionale necessario per il suo stile artistico? Come riesce a contenere la sua indole vivace all’interno di un modo di fare arte quasi scientifico nella sua realizzazione? La mia espressività è stata molto importante nella pittura libera, ma in quella attuale il lavoro artistico svolge un ruolo subordinato. Le condizioni essenziali del mio processo creativo sono

il riposo, la pazienza e il tempo per il lavoro mentale perché la fretta o un eccessivo dinamismo tendono ad essere controproducenti nel lavoro manuale. Non mi rendo conto di irradiare qualcosa di vivace all’esterno. La definizione di vivace comprende molte sfaccettature. Intendo dire che la prudenza, la riflessione, la quieta gioia o la sana umiltà, il desiderio di mettersi in discussione sono anche una forma di essere vivace dal punto di vista mentale. Nella mia arte riesco a conciliare sia il mio lato razionale che quello emotivo perché l’arte dà libertà alle mie emozioni. A volte al contrario, sono giudicato persino introverso. Il lavoro artistico è la mia vita, la mia passione e la mia realizzazione. Nel mio studio mi sento libero di osservare, contemplare, ricercare, riconoscere, sperimentare e imparare a capire le connessioni e le nuove. Questa è l’ispirazione che sviluppa la mia creatività.

Quanto conta la forma geometrica in un mondo in cui sembrano essere stati persi tutti i riferimenti e in cui l’uomo si sente spesso destabilizzato e impaurito? Può essere il suo un modo per suggerire all’individuo che forse tornare alla basicità e alla semplicità è la via migliore per ritrovare il proprio centro esistenziale?

Viviamo in un mondo di forme geometriche, superfici, corpi e spazi. tutti adempiono a uno scopo specifico, sono gravati di senso e significato, ci travolgono in parte e tuttavia hanno un fascino a cui è difficile resistere. Qualcosa si accende, si innesca, suona o ringhia, spingendoci a fare questo o quello o lasciare. Bloccati in tutti questi sistemi, ci occupiamo dell’origine, della natura perdute. Desideriamo riposo e relax. Poi ci prendiamo le vacanze, viaggiamo in altri paesi per rilassarsi. Ma non appena giungiamo in un bel posto, prendiamo in mano lo smartphone per condividere e ritrovare il nostro appagamento, quello di sempre, noi la sera davanti a un rettangolo tremolante.

Al contrario, le mie sculture sono statiche. Non hanno significato, nessuno scopo, la figura geometrica non pretende nulla, irradia solo il silenzio. Anche se noi artisti curiamo ogni lavoro per attribuire un significato o uno scopo, come se dovessimo giustificarci, non cambia nulla del loro essere. Forse le mie sculture possono creare uno spazio libero in cui lo spettatore è solo un essere umano, può essere come vuole, può pensare quello che vuole, non deve fare niente, gli oggetti non esigono niente, sono semplicemente lì e dovrebbero invitare le persone a riconoscere, a capire, a calmarsi. Immagino che i miei oggetti occupino lo spazio, mettendosi in scena: “Qui ci sono io, guardami”, come una rosa che diffonde il suo profumo.

A quale dei grandi maestri del Novecento si sente più vicino o si è ispirato per dare vita al suo stile scultoreo? E quanto la sperimentazione con diversi e innovativi materiali è importante per proseguire la ricerca anticipata da quei grandi maestri?

Nella fase del mio riorientamento artistico sono rimasto affascinato dallo scultore Klaus Kammerichs, dalla sua tecnica nel creare sculture, in particolare il suo straordinario approccio all’opera. Non volevo semplicemente copiarlo come facevo con i vecchi maestri della pittura di strada, piuttosto, ho cercato un’opportunità nell’osservare lo sviluppo delle sue pratiche per utilizzarle nei miei oggetti geometrici. Ho fatto alcuni tentativi con semplici geometrie tuttavia gli elementi non si sono incontrati a causa dei diversi materiali che utilizzavo così non sono andato

oltre la fase sperimentale. L’artista M.C. Escher mi ha conquistato con i suoi lavori di stanze inclinate, scale e oggetti impossibili; lui aveva studiato matematica e doveva rendersi conto che quella scienza non lo infastidiva nel suo lavoro artistico, al contrario gli ha portato beneficio e ha accresciuto il suo originale successo. Anche Piet Mondrian ha sempre attratto il mio interesse con le sue composizioni di rettangoli e quadrati, con quei colori ridotti che ricordano più l’architettura, affascinanti nella loro semplicità. L’idea di creare oggetti walk-in in questo modo ha dato le ali

alla mia immaginazione. Sono stato una volta al Burning Man, un festival nel deserto del Nevada dove si esibiscono vari artisti e gli architetti partecipanti hanno creato sculture e oggetti fantastici, mi sono sentito ammirato dalle loro opere. Il mio lavoro riguarda la sperimentazione di superfici, corpi e spazi in primo piano e i requisiti di resistenza e stabilità determinano il materiale; lavoro principalmente con legno e compositi di legno perché amo questi materiali. Uso i metalli solo per gli elementi di fissaggio perché non li amo particolarmente; recentemente sto sperimentando il plexiglass per i miei oggetti luminosi e forme spaziali. Per me, questo polimero ha un grande potenziale sia per il colore che per l’impatto visivo.

Lei partecipa regolarmente a molte mostre in Germania e all’estero, ricevendo molti consensi dal pubblico e dagli addetti ai lavori, quali saranno i prossimi appuntamenti in cui potremo vedere le sue opere?

A causa delle restrizioni del Coronavirus, il lavoro artistico è stato limitato a mostre ed eventi riservati ma non sono stati fatti molti eventi pubblici, però ho gestito la promozione della mia arte su Internet. Nel frattempo mi sono dedicato alla realizzazione di un’idea che era un mio sogno da molto tempo, cioè un libro sul mio lavoro, dai tratti autobiografici, in cui presento la mia arte,

spiego i motivi, le idee e il loro sviluppo; non ho ancora terminato la stesura dunque spero di finirlo presto e trovare un editore verso la fine dell’anno e potrò presentare il libro nel 2023. Inoltre ho in programma una mostra a Saarburg per Pasqua 2023 e successivamente intendo partecipare a diverse mostre collettive. Al momento è tutto ancora in fase di progettazione perché non sono state ancora fissate date esatte. Comunque al momento sto dedicando la maggior parte del mio tempo e delle mie energie a completare il mio libro.

E-Mail: hans_adam@gmx.de

Webseite: https://hansadam.de/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/hans.adam.92

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/hansadam_24/

Marta Lock’s interviews:

Hans Adam, the study of form and his dialogue with his surroundings

German, born in Cologne, but characterised by an eclectic and dynamic personality that goes hand in hand with a more logical and rational attitude precisely because his being an artist makes him enter the dimension of creativity, the dimension where everything is possible, where colour becomes a guide but where experimentation and the desire to go beyond and overcome the knowledge already acquired constitute a functional attitude for the elaboration of the artwork. He indulged his artistic inclination as a boy, Hans Adam, enrolling in the free painting faculty at the University of Cologne, which was followed by professional experience as a multimedia designer. His love for culture is not limited to plastic expression, but he also feels the need to measure himself with other disciplines, such as writing, by virtue of which he became a member of the Saarbrücken Literary Circle. His creative path is therefore multifaceted and inarginable, and manifests itself particularly in his aptitude for experimentation in which he combines geometric forms with the interaction of colours that appear as pieces to be placed in dialogue with one another, highlighting Hans Adam’s capacity for observation, his desire to harmonise the creative impulse with an analytical attitude that almost unconsciously translates into a metaphorical account of contemporary reality. Yes, because his sculptures not only seem to seek their place, their dimension, within the surrounding space, as if the alternation of full and empty spaces that characterises them represented the alternation in daily life of those highs and lows with which each individual inevitably has to contend, but the chromatic juxtaposition visually identifies and emphasises the contrast or contiguity with which the artist describes light and shadow, highlights volumes and narrates the solidity as opposed to the inconsistency that characterises objective reality. The artwork Vier Kreise Modell (Four-Circle Model) perfectly illustrates Hans Adam’s dual approach, that balance between lightness and impressiveness in which the lacquered colour becomes as much a compositional element as the plywood and wood used for the large structure designed to be traversed by man, thus introducing the element of space that is not only something to be found outside but also inside the sculpture, which thus becomes a welcoming symbol of inclusion. In Ohne Titeln 3 (Untitled 3), on the other hand, the artist chooses to extend compositional experimentation and dialogue between different elements that, by virtue of his creative touch, come into perfect harmony; thus wood, Plexiglas, mirror, multiplex, LED and lacquered colour make up a sculpture in which space once again enters inside to lighten its volumes, but at the same time instils in the observer a sense of concreteness, of elegant solidity given by the alternation of light and colour through which Hans Adam seems to suggest going beyond appearances, to enter the surface, made up of the outermost volumes, to then discover how much more is hidden behind them. In the artist’s creative approach, therefore, what counts is the geometric basis that becomes a means of research, of an in-depth study of matter and chromaticity, of their dialogue and relationship with the outside world, and only later, contrary to Adam’s intention and concept that art should not have a connection with the inner world, that experimentation becomes a metaphor for the world around him, allowing him to bring out contradictions and aspects of contemporary living that are only apparently aseptic and devoid of emotionality but in reality much more substantial than he believes he has to prove himself to be. Let us now get to know this dynamic sculptor better through the interview questions.

Hans, you have followed your creative impulse since your youth, which allowed you to experiment in your artistic career, following which you chose to adhere to Geometric Abstractionism. Why this choice? Was it a reasoned point of arrival or did it come spontaneously following your creative instinct?

The motivations that led me to my current style are many. When I was at school, painting was like a kind of language for me, and as a child, at the age of six or seven, I already knew that I wanted to be a painter. Despite the resistance I found in my family environment, I managed to study painting after my professional training as a gardener. Even during my studies, I exhibited the copies I made of the artworks of the great masters like Rembrandt, Van Dyck and Rubens and this allowed me to finance part of my studies, to buy paints and other painting utensils. A few years later, searching for new paths, I came to a point where I questioned my painting. That was the turning point in my life. I felt the need to see the world, I went to India and Bali where I worked mainly in handicrafts. With all the new experiences and overwhelming impressions from foreign worlds, I discovered new possibilities to express my creativity. Geometric shapes, surfaces, bodies, spaces, their interactions, this was what fascinated me. I felt playfully transported back to my childhood days and was stimulated by being able to create those shapes with art that attracted me as a child, the different facets of geometry were, and still are, irresistible. The experimentation and physical perception of elements and spaces, as well as the creative act involved, give me great fulfilment and deep satisfaction.

You have a very dynamic and eclectic personality, how do you reconcile this aspect of your character with the logical and rational approach required for your artistic style? How do you manage to contain your lively nature within an almost scientific way of making art?

My expressiveness has been very important in free painting, but in my current artwork it plays a subordinate role. The essential conditions of my creative process are rest, patience and time for mental work because haste or excessive dynamism tend to be counterproductive in manual work. I do not realise that I radiate something lively externally. The definition of lively encompasses many facets. I mean that prudence, reflection, quiet joy or healthy humility, the desire to question oneself are also a form of being mentally lively. In my art, I manage to reconcile both my rational and emotional side because art gives freedom to my emotions. Sometimes, on the contrary, I am even judged to be introverted. Art work is my life, my passion and my fulfilment. In my studio I feel free to observe, contemplate, research, recognise, experiment and learn to understand connections and new ones. This is the inspiration that develops my creativity.

How important is geometric form in a world where all references seem to have been lost and where man often feels destabilised and afraid? Could his be a way of suggesting to the individual that perhaps returning to basicity and simplicity is the best way to find one’s existential centre?

We live in a world of geometric shapes, surfaces, bodies and spaces. they all fulfil a specific purpose, they are burdened with meaning and significance, they overwhelm us to some extent and yet have a fascination that is difficult to resist. Something ignites, triggers, rings or growls, urging us to do this or that or leave. Stuck in all these systems, we deal with the origin, the lost nature. We long for rest and relaxation. Then we take holidays, we travel to other countries to relax. But as soon as we arrive in a beautiful place, we pick up the smartphone to share and regain our contentment, the one we always had, us in the evening in front of a flickering rectangle.

On the contrary, my sculptures are static. They have no meaning, no purpose, the geometric figure claims nothing, it only radiates silence. Although we artists treat each work to attribute meaning or purpose, as if we had to justify ourselves, it does not change anything about their being. Perhaps my sculptures can create a free space where the viewer is just a human being, he can be as he wants, he can think what he wants, he does not have to do anything, the objects do not demand anything, they are simply there and should invite people to recognise, to understand, to calm down. I imagine my objects occupying space, staging themselves: ‘Here I am, look at me’, like a rose spreading its perfume.

Which of the great masters of the 20th century do you feel closest to or have been inspired by when creating your sculptural style? And how important is experimentation with different and innovative materials to continue the research anticipated by those great masters?

In the phase of my artistic reorientation, I was fascinated by the sculptor Klaus Kammerichs, his technique in creating sculptures, and in particular his extraordinary approach to the artwork. I did not want to simply copy him as I did with the old masters of street painting, rather, I looked for an opportunity in observing the development of his practices to use them in my geometric objects. I made some attempts with simple geometries however the elements did not meet because of the different materials I was using so I did not go beyond the experimental phase. The artist M.C. Escher won me over with his artworks of tilted rooms, staircases and impossible objects; he had studied mathematics and must have realised that this science did not bother him in his artistic work, on the contrary it benefited him and increased his original success. Piet Mondrian also always attracted my interest with his compositions of rectangles and squares, with those reduced colours more reminiscent of architecture, fascinating in their simplicity. The idea of creating walk-in objects in this way gave wings to my imagination. I was once at Burning Man, a festival in the Nevada desert where various artists performed and the participating architects created fantastic sculptures and objects, I felt admired by their work. My work is about experimenting with surfaces, bodies and spaces in the foreground and the requirements of strength and stability determine the material; I work mainly with wood and wood composites because I love these materials. I only use metals for fasteners because I do not particularly love them; recently I have been experimenting with Plexiglas for my light objects and spatial forms. For me, this polymer has great potential for both colour and visual impact.

You regularly take part in many exhibitions in Germany and abroad, receiving much acclaim from the public and insiders, what are the next events where we will be able to see your work?

Due to the restrictions of the Coronavirus, artistic work has been limited to private exhibitions and events, but not many public exhibitions have been held, so I have been dedicated in managing the promotion of my art on the Internet. In the meantime, I focused myself to realising an idea that had been a dream of mine for a long time, namely a book about my work, with autobiographical traits, in which I present my art, I explain the motives, ideas and their development; I have not yet finished the drafting so I hope to finish it soon and find a publisher towards the end of the year to be able to present the book in 2023. In addition, I am planning an exhibition in Saarburg for Easter 2023 and afterwards I intend to participate in several group exhibitions. At the moment everything is still in the planning stage because no exact dates have been set yet. However, at the moment I am devoting most of my time and energy to completing my book.