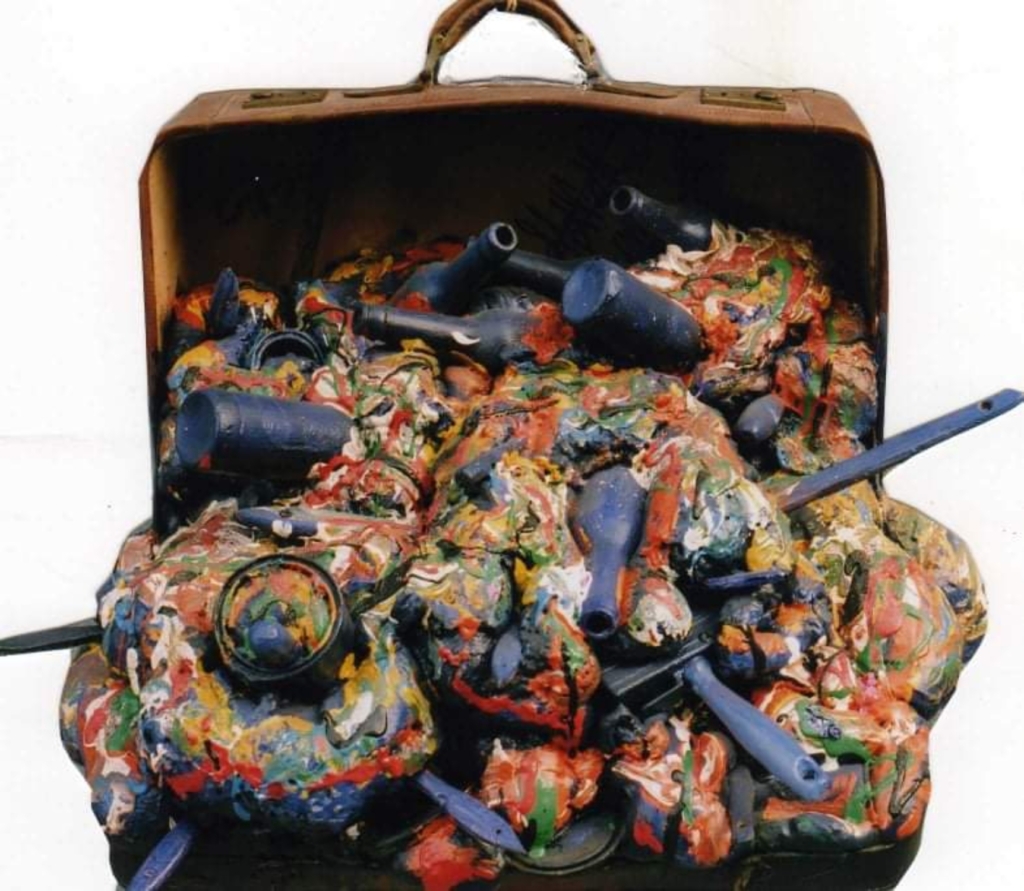

Malgrado la sua formazione più tecnica che artistica, ha conseguito il diploma di perito agrario, l’inclinazione creativa è rimasta una costante del suo percorso che gli ha impedito di lasciare in disparte quella necessità espressiva a cui ha dovuto cedere, si è dovuto arrendere proprio perché comunicare le proprie sensazioni, il proprio punto di vista sulla realtà che lo circonda è sempre stata una parte importante della sua vita. Il coraggio di intraprendere un cammino complesso e incerto è stato premiato nel 1998, circa dieci dopo aver cominciato a esporre le sue opere in Italia e all’estero, quando cioè ha avuto la fortuna di incontrare quello che è ancora oggi uno dei suo maggiori collezionisti e che lo ha costantemente incoraggiato a perseguire il suo sogno artistico affiorato inizialmente come amore verso il disegno e la pittura fin da bambino e continuato con un’evoluzione che lo ha avvicinato al Dadaismo per la sua attrazione verso l’estetica dell’oggetto, il fascino del riutilizzo che nasconde non solo un’attenzione nei confronti del riciclo e dunque della possibilità di trasformare qualcosa che diversamente terminerebbe il suo corso di vita, ma a un livello più profondo svela anche uno sguardo attento e critico sulla società contemporanea. Nato a Cremona ma residente a Crema, Adolfo Maffezzoni divide la sua vita tra il suo essere marito e padre e il suo essere un’artista, pertanto le riflessioni filosofiche che emergono dalle sue opere sono riconducibili anche alle legittime perplessità come genitore, preoccupato di dove stia andando il mondo in cui vivranno i suoi figli, sebbene in lui sia evidente l’approccio derisorio e smitizzante che si lega indissolubilmente ai suoi predecessori Dada ma che li oltrepassa dal punto di vista del significato, del senso, poiché mostra un interesse più sottile nella sostanza di tutto ciò che appartiene alla vita. I tempi moderni sono diversi da quelli in cui il movimento era nato, sono più superficiali e pertanto hanno bisogno di maggiore analisi, approfondimento e osservazione di quei fenomeni emergenti che sembrano destinati ad accompagnare l’umanità molto a lungo. L’opera Apertura

appare come un accumulo informe di rottami, di oggetti ormai inutili e riposti distrattamente all’interno di una valigia vecchia, come se anche lei si sommasse alle cose da buttare; d’altro canto però quella stessa valigia può rappresentare lo scrigno dell’esperienza, del tempo passato che induce a portarsi dietro le pesanti zavorre costituite da fratture, dolori, difficoltà ma anche di emozioni, sensazioni raccontate dalla massa magmatica di colore variopinto. Da un lato Maffezzoni evidenzia così la tendenza all’accumulo stimolata dalla cultura consumistica iniziata negli anni Cinquanta del Novecento ed evoluta in nuove forme nell’attualità, dall’altro invece suggerisce quanto per qualcuno possano essere rassicuranti gli oggetti che hanno accompagnato e contrassegnato l’esistenza. Nella tela Feci colorate,

in cui mescola la pittura all’elemento materico, l’artista ironizza sulla capacità della pubblicità di rendere affascinante anche qualcosa che se vista nella sua vera natura sarebbe tutt’altro che desiderabile; l’immagine accattivante che dà il titolo all’opera mette in secondo piano lo sfondo rappresentante un gabinetto alla turca funzionale però a lasciar evincere all’osservatore la realtà del soggetto. L’intento di Adolfo Maffezzoni è quello di mettere in luce l’aspetto effimero del vivere attuale, quell’orientarsi costantemente verso la patina lucente, l’involucro che troppo spesso ha un contenuto ben differente da quello immaginato; pertanto il suo invito all’osservatore è quello di meditare su questo aspetto della realtà, di spingersi oltre e andare a verificare ciò che viene proposto perfettamente impacchettato, prima di lasciarsi incantare dal suo aspetto esteriore. Moltissimi i materiali utilizzati per dar vita alle sue opere appartenenti a quella che lui definisce estetica del rottame, pezzi di quadro distrutti, camicie, lattine, sacchi di juta, pennelli vecchi, poliuretano, cartapesta, bottiglie, legni fresati, carte stazzonate, corde, valigie, piatti di cartone, che diventano mezzi per esprimere i concetti essenziali. Andiamo ora a scoprire di più di questo dissacrante artista.

Adolfo, la sua formazione non è stata artistica eppure ha sempre manifestato un’inclinazione naturale che l’ha spinta a raccogliere la sfida e a crearsi la sua strada nel mondo dell’arte. Qual è stato il momento cruciale che le ha fatto decidere di dare un seguito al suo istinto espressivo? E quando ha deciso che la sua creatività aveva bisogno di misurarsi con la materia?

Penso che la mia sia stata una scelta dettata dalla sensibilità, dall’ascolto del mio io interiore, che è poi il motivo per il quale ognuno di noi predilige un percorso invece di un altro. Il momento cruciale e preciso è stata una specie di folgorazione in piazza della pace a Cremona: era una sera estiva dell’anno 1984, ero assorto nei miei pensieri e meditavo su quale cammino intraprendere nella vita, cosa fare, e all’improvviso ho sentito che volevo fare il pittore. Dopo le prime esperienze pittoriche ho avvertito l’esigenza di depurare la mia arte da tutto ciò che era tradizionale, da un approccio già visto e dai concetti comuni, epurandola del risaputo.

Quanto è importante per lei avere uno sguardo disincantato e irriverente nei confronti della realtà contemporanea? Crede che il messaggio che arriva all’osservatore in maniera indiretta sia poi in grado di indurre una riflessione più profonda?

Il lavoro di un artista è una testimonianza, è un approccio originale nei confronti della realtà perché di fatto interpreta l’oggettivo attraverso il soggettivo, dunque ciascuno ha il proprio punto di vista; nel mio caso uno sguardo irrisorio e ironico è il mezzo per esprimere messaggi che diversamente potrebbero apparire polemici, critici. Attraverso l’irriverenza esco dalle sensazioni negative pur senza rinunciare a lasciar trapelare quel messaggio che vorrei far uscire. Dopotutto il primo osservatore del suo lavoro è lo stesso artista che cerca, attraverso i suoi lavori, di dar voce alla sua riflessione più o meno profonda e solo in un secondo tempo il messaggio magicamente giunge all’osservatore. A quel punto si genera un contatto energetico, un’emozione più o meno razionale tra chi comunica e chi riceve.

Il suo utilizzo di materiali in disuso, rottami e oggetti che verrebbero gettati, la avvicina alla filosofia dell’arte del riciclo sebbene lei definisca il suo approccio estetica del rottame. Ci vuole approfondire questo concetto? Lei realizza anche installazioni, ci illustra quella sul terreno di un suo amico sulla statale 415?

L’uso dei materiali in disuso è nato quando decisi di distruggere le prime opere in quanto troppo affini nello stile a movimenti tradizionali del passato, eseguivo repliche di opere realiste, chiariste, impressioniste, surrealiste e grafiche; da questa epurazione sono nati dei collage di tele distrutte che solo in un secondo tempo sono poi evolute verso un approccio materico attraverso l’integrazione di materiale polimaterico con valenza simbolica. L’estetica del rottame ha origine fin dai tempi della Caverna di Altamira in quanto l’artista preistorico usò per le rappresentazioni cinetiche delle scene di caccia materiali di fortuna, roccia e colori organici. Con l’evolversi dell’uomo e delle tecniche artistiche si è passati a materie tecnicamente più sofisticate che rappresentavano personaggi infimi come le prostitute pompeiane, o perseguitati, folli, straccioni, come nelle opere di Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel, Francisco Goya, Zoran Mušič, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Renzo Vespignani, Anselm Kiefer. La prima installazione prospiciente la statale 415 è stata realizzata nel 1999 e intitolata Segnali di confine a dimostrazione dell’autorevolezza di un segnale. Nel 2000 l’installazione Sulle tracce di Moby Dick rappresentava l’instancabile ricerca dell’assoluto che l’uomo insegue. Nel 2003 Pronti per il decollo 17 12 1903-17 12 2003 è stata dedicata al centenario del primo decollo aereo, conquista dello spazio. E poi ancora nel 2004 ho creato Cactus simbolo di affinità alle mie opere come esempio di accumulazione. Nel 2009 Cavalli di frisia rappresentò una difesa non solo bellica, ambientale, ma anche simbolica perché anche l’esperienza è una difesa. E poi nel 2015 ho ideato Gradevolmente macabro, esposizione di sagome di buoi squartati, ispirandomi al bue macellato di Rembrandt a cui ha seguito il periodo delle camicie e delle valige come escavazione dell’intimo. Infine nel 2019 è stata la volta di Fuoco in bocca legato alla scoperta del fuoco, e la meditazione davanti a esso. Insomma le installazioni sono messaggi e al tempo stesso un modo per attingere idee per successive produzioni di opere, segnano l’inizio di un nuovo percorso.

Attraverso la rivisitazione e riattualizzazione delle tematiche del Dadaismo lei sottolinea e mette in evidenza le insidie e i disagi del vivere contemporaneo; quali sono gli artisti del passato a cui si ispira? Quali sente più vicini per tematiche e per intento espressivo?

Sono un grande ammiratore di Rembrandt, di Duchamp per il ready made, di Rauschenberg e Jasper Johns perché sono artisti spiccatamente Dada. Ma quelli che forse si avvicinano di più al mio approccio e all’attenzione verso i temi sociali e anche per l’impatto visivo delle loro opere sono Joseph Beuys e Anselm Kiefer.

Ha al suo attivo molte mostre personali e collettive in Italia e nel mondo, oltre a vantare numerosi collezionisti che si pregiano di avere in casa le sue opere; ci racconta quali sono i suoi prossimi progetti?

Attualmente sto lavorando alla realizzazione di un cancello.

ADOLFO MAFFEZZONI-CONTATTI

Email: adolfomaffezzoni@libero.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100004475686483

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/adolfomaffezzoni/

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/adolfo-maffezzoni-84325a43/

Marta Lock’s interviews: Adolfo Maffezzoni, when objects stop being useful and become art

Despite his training being more technical than artistic – he has a diploma as an agricultural expert – his creative inclination has remained a constant in his path, which has prevented him from leaving aside that need for expression to which he has had to give in, he has had to surrender precisely because communicating his own sensations, his own point of view on the reality around him, has always been an important part of his life. His courage to embark on a complex and uncertain path was rewarded in 1998, some ten years after he began exhibiting his artworks in Italy and abroad, when he had the good fortune to meet the man who is still one of his biggest collectors today and who has constantly encouraged him to pursue his artistic dream that first surfaced as a love of drawing and painting as a child and continued with an evolution that brought him closer to Dadaism because of his attraction to the aesthetics of the object, the fascination with reuse that conceals not only an attention to recycling and thus the possibility of transforming something that would otherwise end its life, but at a deeper level also reveals a careful and critical look at contemporary society. Born in Cremona but residing in Crema, Adolfo Maffezzoni divides his life between being a husband and father and being an artist, so the philosophical reflections that emerge from his works can also be traced back to his legitimate perplexities as a parent, concerned about where the world in which his children will live is heading, although in him is evident the derisive and demythologising approach which is inextricably linked to his Dada predecessors but which goes beyond them in terms of meaning, in that it shows a more subtle interest in the substance of everything in life. Modern times are different from those in which the movement was born, they are more superficial and therefore need more analysis, insight and observation of those emerging phenomena that seem destined to accompany humanity for a very long time. The work Aperture appears as a shapeless accumulation of wreckage, of objects that are now useless and placed absent-mindedly inside an old suitcase, as if it too were added to the things to be thrown away; on the other hand, however, that same suitcase may represent the treasure chest of experience, of time past that induces one to carry around the heavy ballast made up of fractures, pain, difficulties, but also of emotions, sensations told by the magmatic mass of multicoloured colour. On the one hand, Maffezzoni thus highlights the tendency to accumulate stimulated by the consumer culture that began in the 1950s and has evolved into new forms in the present day, while on the other hand he suggests how reassuring the objects that have accompanied and marked existence can be for some. In the canvas Coloured Faeces, in which he mixes painting with the material element, the artist is being ironic about the ability of advertising to make fascinating even something that if seen in its true nature would be anything but desirable; the captivating image that gives the artwork its title overshadows the background representing a Turkish-style toilet, which, however, serves to allow the observer to see the reality of the subject. Adolfo Maffezzoni’s intention is to highlight the ephemeral aspect of present-day living, that constant orientation towards the shiny patina, the wrapping that all too often has a content quite different from that imagined; therefore his invitation to the observer is to meditate on this aspect of reality, to go further and verify what is proposed perfectly packaged, before allowing himself to be enchanted by its external appearance. Several are the materials he uses to give life to his works belonging to what he calls the aesthetics of scrap, pieces of destroyed paintings, shirts, tin cans, jute sacks, old paintbrushes, polyurethane, papier-mâché, bottles, milled wood, stained paper, ropes, suitcases, cardboard plates, which become means to express essential concepts. Let us now discover more about this desecrating artist.

Adolfo, your training was not artistic, yet you have always shown a natural inclination that led you to take up the challenge and create your own way in the art world. What was the crucial moment that made you decide to follow up on your expressive instinct? And when did you decide that your creativity needed to measure itself with matter?

I think mine was a choice dictated by sensitivity, by listening to my inner self, which is why each of us prefers one path instead of another. The crucial and precise moment was a kind of electrocution in Piazza della Pace in Cremona: it was a summer evening in 1984, I was absorbed in my thoughts and meditating on which path to take in life, what to do, and suddenly I felt that I wanted to be a painter. After my first experiences as a painter, I needed to purge my art of everything that was traditional, of a previously seen approach and common concepts, purging it of the familiar.

How important is it for you to have a disenchanted and irreverent look at contemporary reality? Do you believe that the message that reaches the observer indirectly is then able to induce deeper reflection?

The work of an artist is a testimony, it is an original approach to reality because it actually interprets the objective through the subjective, so everyone has his own point of view; in my case a derisory and ironic look is the means to express messages that otherwise might appear polemical, critical. Through irreverence I get out of negative feelings without giving up the message I would like to get out. After all, the first observer of his work is the artist himself who tries, through his artworks, to give voice to his more or less profound reflection and only later does the message magically reach the observer. At that point an energetic contact is generated, a more or less rational emotion between the communicator and the receiver.

Your use of disused materials, scrap and objects that would be thrown away, brings you closer to the philosophy of the art of recycling, although you define your approach as scrap aesthetics. Would you like to elaborate on this concept? You also create installations, would you illustrate the one on your friend’s land on State Road 415?

The use of discarded materials was born when I decided to destroy the first paintings as they were too similar in style to traditional movements of the past, I executed replicas of realist, chiarist, impressionist, surrealist and graphic works; from this purge came collages of destroyed canvases that only later evolved towards a material approach through the integration of polymaterial with symbolic value. The aesthetics of wreckage originated as far back as the Cave of Altamira in that the prehistoric artist used makeshift materials, rock and organic colours for kinetic representations of hunting scenes. As mankind and artistic techniques evolved, they moved on to more technically sophisticated materials depicting lowly characters such as Pompeian prostitutes, or the persecuted, the insane, the ragged, as in the works of Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel, Francisco Goya, Zoran Mušič, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Renzo Vespignani, and Anselm Kiefer.

The first installation facing State Road 415 was realised in 1999 and entitled Border Signals, demonstrating the authoritativeness of a signal. In 2000, the installation On the trail of Moby Dick represented man’s tireless search for the absolute. In 2003 Ready for take off 17 12 1903-17 12 2003 was dedicated to the centenary of the first air take-off, the conquest of space. And then again in 2004 I created Cactus as a symbol of affinity to my works as an example of accumulation. In 2009 Friesian Horses represented a defence not only of war, the environment, but also symbolic because experience is also a defence. And then in 2015 I came up with Pleasantly macabre, an exhibition of silhouettes of quartered oxen, inspired by Rembrandt’s butcher’s ox, which was followed by the period of shirts and suitcases as an excavation of underwear. Finally, in 2019 it was the turn of Fire in the Mouth linked to the discovery of fire, and meditation in front of it. In short, the installations are messages and at the same time a way to draw ideas for subsequent productions of works, marking the beginning of a new path.

By revisiting and updating the themes of Dadaism, you emphasise and highlight the pitfalls and discomforts of contemporary living; which artists from the past do you draw inspiration from? Which ones do you feel are closest in terms of themes and expressive intent?

I am a great admirer of Rembrandt, of Duchamp for the ready-made, of Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns because they are distinctly Dada artists. But those who perhaps come closest to my approach and attention to social issues and also for the visual impact of their works are Joseph Beuys and Anselm Kiefer.

You have many solo and group exhibitions to your credit in Italy and around the world, as well as numerous collectors who are proud to have your artworks in their homes; can you tell us what are your next projects?

I am currently working on the construction of a gate.