La formazione come autodidatta ha costituito il modo per non avere alcuna regola, alcun limite né tanto meno alcun condizionamento dal punto di vista stilistico, e anche per quella sua particolare attitudine a creare da solo gli strumenti fondamentali per la sua pittura; il percorso successivo attraverso il quale ha avvertito il bisogno di approfondire la conoscenza dell’arte così come dei maestri del passato, hanno avviato la costruzione di una maggiore consapevolezza e necessità di unire le caratteristiche distintive di alcuni tra i suoi artisti preferiti per cercare una strada che fosse solo sua, che gli permettesse di essere riconoscibile ma anche di armonizzarsi con la propria personale natura espressiva che aveva bisogno di emergere. I numerosi viaggi in India hanno permesso ad Achao di andare in fondo a se stesso, scoprendo una sorprendente spiritualità, la medesima che gli ha permesso di dare vita al suo stile più recente in cui l’impalpabilità e l’immaterialità sottolineano l’esigenza inconscia dell’individuo contemporaneo di trovare una connessione con l’anima, con un’interiorità troppo spesso trascurata e proprio per questo necessitante di liberare una via per far sentire la propria voce. Dunque dopo aver seguito i corsi serali di scultura e disegno delle Belle Arti della città di Parigi e aver studiato e selezionato le personalità artistiche del passato in grado di fornirgli maggiori spunti creativi perché più affini al suo modo di vedere e vivere l’arte, Achao comincia a dare struttura a una cifra stilistica vicina all’Espressionismo ma tendente, soprattutto con il passare del tempo e con lo strutturarsi del suo percorso spirituale, verso un Espressionismo Astratto in cui più che l’irruenza espressiva emerge un’istintualità moderata dal tendere verso la ricerca di una serenità e un equilibrio che possono essere raggiunti solo nel momento in cui la spontaneità del sentire si unisce alla consapevolezza della propria forza interiore e la capacità di camminare all’interno di entrambi. È questa l’esortazione dell’artista, quella di lasciarsi andare al fluire delle energie interiori che si armonizzano alla natura, intesa come naturalezza, e permettere a tutto ciò che ruota intorno al sé di entrare e far vibrare le corde interiori, di scuotere con delicatezza la coscienza per indurla a trovare il senso di definitezza accettando la propria imperfezione e limitatezza. Uno degli artisti che più lo ispirano è Henri Matisse nella sua fase più matura, quella in cui la figurazione lasciò spazio alla stilizzazione e a un ritorno alla natura divenuta protagonista nel suo pensiero e nel suo approccio stilistico; tanto quanto Matisse, non più in grado di dipingere, ritagliava dei cartoncini per realizzare le sue opere, altrettanto Achao realizza gli stencil attraverso cui dar vita ai suoi dipinti su cui opera con colori acrilici su tela libera infondendo al risultato finale un effetto plastico, concreto e consistente, quasi in contrasto con la leggerezza delle immagini e con la gamma cromatica pastello, impalpabile, che infonde nell’osservatore un senso di pace e il desiderio di immergersi nelle atmosfere fluide dell’artista.

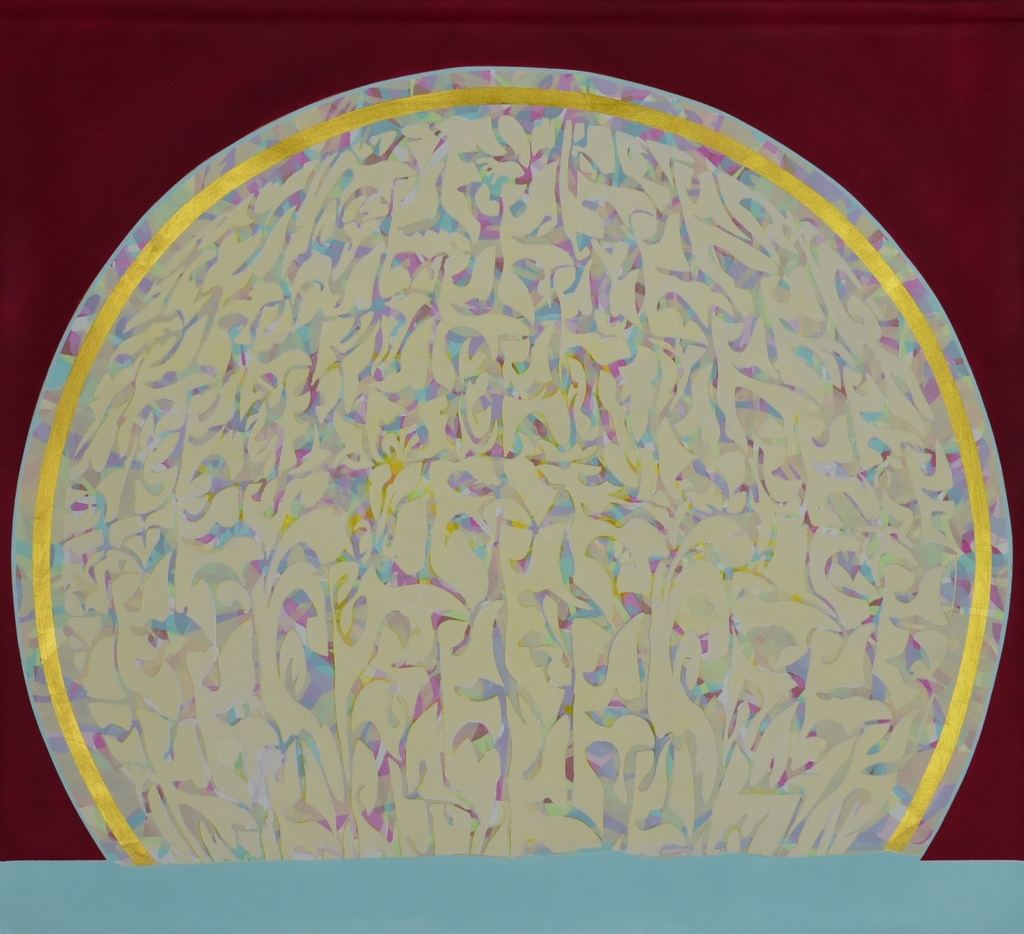

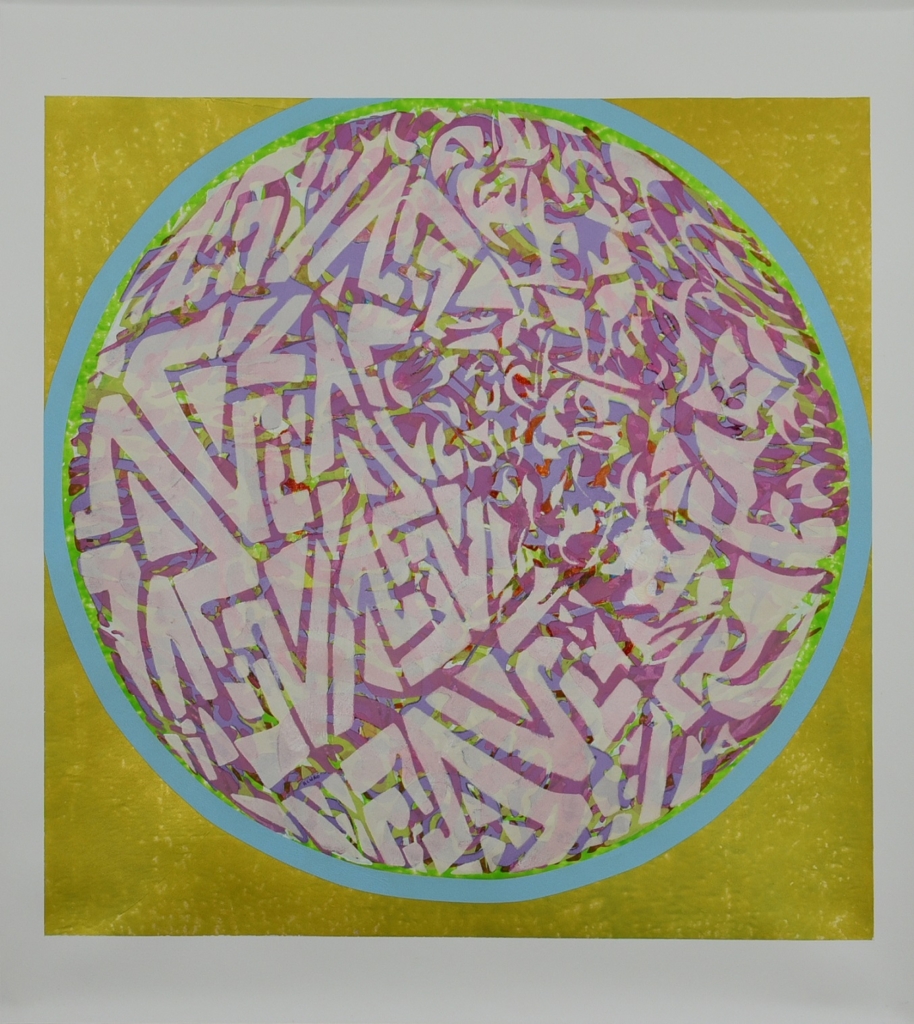

Uno dei temi prediletti è quello della solennità dei templi indiani Dhamek Stupa di Sarnath che fuoriescono in maniera sussurrata dalle opere della serie Impermanence dove la forma sferica è un chiaro riferimento alla struttura dei templi indiani ma anche alla simbologia spirituale del buddismo dove la sfera rappresenta il compimento, uno stimolo a tendere verso una costante evoluzione in grado di infondere maggiore saggezza proprio in virtù dell’approfondimento e la conoscenza del sé. E in fondo il cerchio contraddistingue anche i corsi e ricorsi che si continueranno a presentare a meno che l’individuo non prenda coscienza e osservi i propri errori, le proprie cadute trovando il senso più profondo agli accadimenti e l’insegnamento che le circostanze, non dunque il caso, indicano.

Tutto questo viene solo suggerito da Achao come un percorso possibile, come una strada in grado di generare quel cambiamento interiore che l’uomo contemporaneo cerca senza sapere come attuare. Andiamo ora ad approfondire la conoscenza di questo originale artista.

Achao, lei si è formato da autodidatta ma poi ha scelto di approfondire e perfezionare la sua tecnica frequentando dei corsi di scultura e di disegno; quanto è importante mantenere la propria autonomia espressiva nell’elaborazione e nella scelta del linguaggio pittorico? Crede che gli studi accademici possano in qualche modo condizionare la creatività limitandone la libera manifestazione?

In effetti, sono un autodidatta. La mia ricerca artistica passa attraverso l’invenzione dei miei strumenti, della mia tecnica e dei miei protocolli di creazione. Inventare una tecnica personale mi ha permesso di impostare una singolare espressione pittorica. Gli studi accademici dei tempi antichi sono stati utili per conoscere l’intera gamma delle possibilità. Per quanto mi riguarda invece, ho dovuto impararlo da solo, inventando e facendo tentativi. Oggi sono un po’ cauto riguardo agli studi artistici, almeno per la Francia dove vivo. Ho l’impressione che la tecnica venga sacrificata a favore della ricerca di una forzata singolarità. Sembra esserci spazio solo per idee concettuali piatte che trattano argomenti spesso ridicoli… Onestamente, le nuove idee sono davvero rare, sono diamanti! Affermare di avere un’idea davvero sostanziale non significa forse fare prima di tutto un’esperienza di vita, saper cogliere un’intuizione, e poi saper tradurre questa idea in un oggetto artistico intelligibile?

L’arte per lei è legata alla spiritualità intesa come cammino di vita e approfondimento della conoscenza. Questa sua filosofica pittorica è stata un punto di arrivo oppure già fin dall’inizio ha sentito di dover sottolineare questa magica unione tra estetica, intesa nel senso più ampio del termine, ed essenza dell’essere? Quanto è stato fondamentale l’incontro con il buddismo per accrescere la sua maturità artistica?

L’emancipazione spirituale è l’intero soggetto della mia pittura. È un incontro avvenuto a mia insaputa all’età di diciannove anni durante un primo viaggio in India. Durante la visita al sito buddista di Sarnath, la mia attenzione è stata subito catturata dai bassorilievi che ornano la parte superiore del Dhāmek Stūpa. Ho fotografato questo bassorilievo in tutti i suoi dettagli come un archeologo farebbe con un inventario. In seguito sono tornato molto regolarmente a Sarnath. Il bassorilievo di Sarnath si è imposto come tema principale della mia pittura. Negli anni ho ridisegnato, ricomposto, reinventato i motivi del suo bassorilievo; immergendomi nello studio del sito di Sarnath, ho capito che si tratta di un luogo eminentemente importante del buddismo, perché è proprio lì che Buddha iniziò a diffondere il suo insegnamento.

Andiamo ora al suo particolare stile pittorico, a cosa è dovuta la scelta della particolare mescolanza tra Espressionismo, Astrattismo e tecniche quasi tribali o di Street Art come la produzione di stencil? Qual è il messaggio che desidera arrivi all’osservatore?

In verità, non mi sento come se avessi il controllo sulla mia tecnica, essa è come un veicolo indipendente che si sviluppa mentre lavoro. L’importante per me è avere una tecnica solida che possa essere oggetto di ricerca artistica.

La mia intenzione è soprattutto quella di parlare al pubblico più vasto. Per me l’arte è un bene pubblico come l’aria e l’acqua. È attraverso un’estetica presunta che desidero raggiungere quante più persone possibile. Se il pubblico ha riferimenti artistici, probabilmente riuscirà a spingere un po’ più in là il piacere di scoprire il mio messaggio. La mia intenzione profonda è quella di immergere gli spettatori nel colore, per offrire loro una sensazione di immersione grazie ai grandi formati. La disposizione dei miei motivi crea uno sguardo fluttuante, offusca leggermente la percezione. Questa impressione di sfocatura invita gli spettatori a scivolare in se stessi verso una dolce introspezione!

Ho l’ingenuità, ma anche la certezza, di credere che sia immergendosi nel profondo che si trovano le risorse e la forza necessarie per inventare i nuovi valori che ci permetteranno di affrontare i futuri tumulti del mondo.

I maestri della storia dell’arte a cui si ispira sono Henri Matisse, Claude Viallat, Alberto Giacometti, Constanti Brancusi. Ci spiega di ognuno cosa ha preso e come lo ha trasformato per dare vita al suo stile?

Claude Viallat è un grande pittore di arte contemporanea, offre una ricerca estetica che lascia spazio al colore, un’enorme varietà di composizioni sulla base di un unico motivo. Allo stesso tempo, dimostra immensa audacia decostruendo i supporti dei suoi quadri! Vorrei trovare nel mio lavoro questo equilibrio tra un’estetica presunta e l’audacia concettuale di Viallat.

Matisse è il grande maestro che ha saputo parlare al pubblico più vasto. In ogni fase della sua vita, ha anche saputo reinventare la sua pratica in modo prodigioso. I suoi fogli ritagliati sono per me fonte di meraviglia. E inoltre, non è forse lui l’artista che ha affermato che esiste solo l’arte spirituale? Sottoscrivo questa affermazione.

Sia Giacometti che Brancusi hanno riscritto totalmente i parametri della scultura del Novecento. Brancusi ha reinventato la disposizione dei materiali e l’intimità tra il soggetto e la base. Applaudo questa ingegnosità. Giacometti capì che non si trattava più di combattere sul terreno dell’anatomia classica, perché Rodin aveva completamente sovvertito questa tematica; ha dunque reinterpretato la figura femminile in un’astrazione divina che lascia spazio all’immaginazione dello spettatore.

Lei ha all’attivo diverse mostre in Francia e in Italia e ha appena aperto il suo nuovo studio. Quali sono i suoi prossimi progetti? Dove potranno vedere le sue opere i lettori?

Trascorro la mia vita nel mio studio, perché preparo diverse mostre personali in Francia e in Italia. Nel mio nuovo atelier mi sento al caldo, come in un bozzolo, ma non mi lascio tentare dalla tentazione di restare al suo interno. A luglio sarò a Quinconces a Vals-les-Bains nel sud dell’Ardèche. Allo Château d’Arthaudiére nell’Isère in agosto. Alla Chapelle des Pénitents Blancs a Gordes a settembre nel Vaucluse. A settembre sono stato invitato alla decima Biennale des Arts Hors Norme di Lione per una mostra all’Università Cattolica. Ad ottobre sarò ad Assisi per una seconda mostra alla Galleria Le Logge, e nel giugno 2024 a Roma alla Galleria Angelica. Spero sinceramente di avere il piacere di incontrare i lettori a queste mostre.

ACHAO ART-CONTATTI

Email: achao-contact@achao.fr

Sito web: http://www.achao.fr/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100009802532411

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/achao.artist/

Marta Lock’s interviews: Achao, the discovery of spirituality through the manifestation of his own personal artistic language

The training as a self-taught artist was a way of having no rules, no limits and no conditioning from a stylistic point of view, and also because of his particular aptitude for creating the fundamental tools for his painting on his own; the subsequent path through which he felt the need to deepen his knowledge of art as well as of the masters of the past, initiated the construction of a greater awareness and need to unite the distinctive characteristics of some of his favourite artists in order to seek a route that was uniquely his own, one that would allow him to be recognisable but also to harmonise with his own personal expressive nature that needed to emerge. Numerous trips to India allowed Achao to get to the bottom of himself, discovering a surprising spirituality, the same that let him give life to his most recent style in which impalpability and immateriality underline the contemporary individual’s unconscious need to find a connection with the soul, with an interiority that is too often neglected and for this very reason needs to free a way to make its voice heard. So after attending evening courses in sculpture and drawing at the Beaux-Arts in Paris and studying and selecting the artistic personalities of the past who could provide him with more creative inspiration because they were more akin to his way of seeing and experiencing art, Achao began to give structure to a stylistic style close to Expressionism but tending especially with the passage of time and the structuring of his spiritual path, towards an Abstract Expressionism in which more than expressive impetuosity emerges an instinctuality moderated by a tendency towards the search for a serenity and balance that can only be achieved when the spontaneity of feeling is united with an awareness of one’s own inner strength and the ability to walk within both. This is the artist’s exhortation, to let go of the flow of inner energies that harmonise with nature, understood as naturalness, and to allow everything that revolves around the self to enter and make the inner chords vibrate, to gently shake the consciousness to induce it to find a sense of definiteness by accepting its own imperfection and limitation. One of the artists who most inspired him was Henri Matisse in his more mature phase, the one in which figuration gave way to stylisation and a return to nature, which became the protagonist in his thinking and stylistic approach; just as Matisse, no longer able to paint, used to cut out cards to create his works, so Achao created stencils to give life to his artworks on which he worked with acrylic paints on free canvas, giving the final result a plastic, concrete and consistent effect, almost in contrast to the lightness of the images and the impalpable pastel colour palette, which instils in the observer a sense of peace and a desire to immerse himself in the artist’s fluid atmospheres. One of his favourite themes is that of the solemnity of the Indian Dhamek Stupa temples of Sarnath, which emerge in a whispering manner from the works in the Impermanence series, where the spherical shape is a clear reference to the structure of Indian temples but also to the spiritual symbolism of Buddhism where the sphere represents fulfilment, a stimulus to strive towards constant evolution capable of instilling greater wisdom precisely by virtue of deepening and knowledge of the self. And after all, the circle also characterises the courses and recurrences that will continue to occur unless the individual becomes aware of and observes his own mistakes, his own downfalls, finding the deeper meaning to the events and the teaching that circumstances, not therefore chance, indicate. All this is only suggested by Achao as a possible path, as a road capable of generating that inner change that contemporary man seeks without knowing how to implement. Let us now get to know this original artist better.

Achao, you trained as a self-taught artist but then chose to deepen and perfect your technique by attending sculpture and drawing courses; how important is it to maintain your own expressive autonomy in the elaboration and choice of pictorial language? Do you believe that academic studies can somehow condition creativity by limiting its free expression?

Actually I’m self-taught. My artistic research goes through the invention of my tools, my technique and my creation protocols. Inventing a personal technique has allowed me to set up a singular pictorial expression. Academic studies from ancient times have been helpful in learning about the full range of possibilities. As far as I’m concerned, I had to learn it by myself, inventing and making attempts. Today I’m a bit cautious about art studies, at least for France where I live. I have the impression that technique is being sacrificed in favor of the search for a forced singularity. There seems to be room only for flat conceptual ideas dealing with often ridiculous topics… Honestly, new ideas are really rare, they are diamonds! Doesn’t claiming to have a truly substantial idea mean first of all having a life experience, knowing how to grasp an intuition, and then knowing how to translate this idea into an intelligible artistic object?

Art for you is linked to spirituality in the sense of a life journey and deepening of knowledge. Was this pictorial philosophy of yours a point of arrival or did you feel from the very beginning that you had to emphasise this magical union between aesthetics, understood in the broadest sense of the term, and the essence of being? How fundamental was your encounter with Buddhism in enhancing your artistic maturity?

Spiritual empowerment is the whole subject of my painting. It is an encounter that took place without my knowledge at the age of nineteen during a first trip to India. While visiting the Buddhist site of Sarnath, my attention was immediately captured by the bas-reliefs that adorn the upper part of the Dhāmek Stūpa. I photographed this bas-relief in all its detail as an archaeologist would take an inventory. I have since returned to Sarnath very regularly. The Sarnath bas-relief has established itself as the main theme of my painting. Over the years I have redesigned, recomposed, reinvented the motifs of his bas-relief; immersing myself in the study of the Sarnath site, I understood that it is an eminently important place of Buddhism, because it is precisely there that Buddha began to spread his teaching.

Let us now turn to your particular painting style, what is the reason for your choice of the particular mix of Expressionism, Abstractionism and almost tribal or Street Art techniques such as stencil production? What is the message you want to reach the viewer?

In truth, I don’t feel like I have control over my technique, it is like an independent vehicle that develops as I work. The important thing for me is to have a solid technique that can be the subject of artistic research.

My intention is above all to speak to the wider public. For me, art is a public good like air and water. It is through an assumed aesthetic that I wish to reach as many people as possible. If the public has artistic references, they will probably be able to push the pleasure of discovering my message a little further. My deepest intention is to immerse viewers in colour, to offer them a feeling of immersion thanks to large formats. The arrangement of my motifs creates a floating gaze, slightly blurs the perception. This impression of blur invites viewers to slide into themselves towards gentle introspection! I have the ingenuity, but also the certainty, of believing that it is by plunging into the depths that we find the resources and strength necessary to invent the new values that will allow us to face the future turmoil of the world.

The masters from the history of art you draw inspiration from are Henri Matisse, Claude Viallat, Alberto Giacometti and Constanti Brancusi. Can you explain what you took from each and how you transformed them to create your style?

Claude Viallat is a great contemporary art painter, he offers an aesthetic research that leaves room for color, an enormous variety of compositions based on a single motif. At the same time, he demonstrates immense audacity by deconstructing the supports of his paintings! I would like to find in my work this balance between an assumed aesthetic and Viallat’s conceptual audacity.

Matisse is the great master who was able to speak to the largest audience. At every stage of his life, he has also been able to reinvent his practice in a prodigious way. His cut sheets are a source of wonder for me. And besides, isn’t he the artist who said that there is only spiritual art? I subscribe to this statement.

Both Giacometti and Brancusi totally rewrote the parameters of 20th century sculpture. Brancusi reinvented the arrangement of materials and the intimacy between the subject and the base. I applaud this ingenuity. Giacometti understood that it was no longer a question of fighting on the terrain of classical anatomy, because Rodin had completely subverted this theme; he therefore reinterpreted the female figure in a divine abstraction that leaves room for the spectator’s imagination.

You have several exhibitions in France and Italy to your credit and you have just opened your new studio. What are your next projects? Where will readers be able to see your artworks?

I spend my life in my studio, because I prepare several personal exhibitions in France and Italy. In my new atelier I feel warm, like in a cocoon, but I don’t let myself be tempted to stay inside. In July I will be in Quinconces in Vals-les-Bains in the south of the Ardèche. At the Château d’Arthaudiére in Isère in August. At the Chapelle des Pénitents Blancs in Gordes in September in the Vaucluse. In September I was invited to the 10th Biennale des Arts Hors Norme in Lyon for an exhibition at the Catholic University. In October I will be in Assisi for a second exhibition at the Galleria Le Logge, and in June 2024 in Rome at the Galleria Angelica. I sincerely hope to have the pleasure of meeting readers at these exhibitions.